|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

ON THE SUBJECT OF LOGIC

|

|

|

|

If the subject of a given science has defined precisely, there are no conflicts with adjacent sciences and no confusion of students. |

|

|

To teach duly any scientific discipline implies that from the very beginning its subject, i.e. its particular sphere of interest, must be defined as much as possible precisely. The strict preciseness is necessary, on the one hand, to avoid expansion into neighbouring sciences and, on the other hand, to cede them nothing of what belongs by right to this concrete science.

Certainly, scientific disciplines are not fenced off from each other by something alike Chinese Wall, but at the outset a teacher, acquainting with fundamentals of a particular science, should outline limits of its subject with the greatest accuracy, "in Chinese style". Dim borders of subjects complicate to students their primary orientation in the realm of science, set them on slippery ground and force to feel extremely uncomfortably. This psychological discomfort of students results either in their confusion, restraint (they don't know what it is necessary to speak about within limits of a given scientific discipline and so, having no desire to put a foot wrong, prefer to keep mum), or in their devil-may-care relaxedness in spirit of Gogol's Khlestakov (they jabber about everything, imagining that only about a given science).

However every teacher, trying to gain the exactest definition of the sphere of direct interest of his scientific discipline, risks to do it so strictly that some integral part of the discipline's subject can appear outside of the borders outlined by him. Excessive rigidity is not less harmful to pedagogical process, than excessive softness, because the both approaches make students to be disoriented.

|

|

|

|

Let's consider how the subject of logic is treated on pages of Russian textbooks. |

|

|

Now let's consider logic so as to investigate how its exclusively original subject is treated on pages of Russian textbooks.

G. Chelpanov in his textbook, written as far back as in 1917, before The October Revolution, says that "logic can be defined as a science about the laws of correct thinking, or about the laws to which thinking submits" [1, 3]. We should make two remarks. Firstly, scientific logic is not the only logic that exists. Personal, homebrew logic has not as a rule a scientific, i.e. objective and system, character, but nevertheless this is, no doubt, logic. Hence, defining logic, we should better speak about knowledge, instead of science. Secondly, a knowledge is considered scientific if that of laws, therefore it is redundant to mention laws, defining logic as a science.

|

|

|

G. Chelpanov

|

The subject of logic, if it has to be expressed as much as possible briefly and precisely, is correct thinking. |

|

|

Once Chelpanov's definition has been changed in view of these remarks, we arrive at understanding of that the subject of scientific logic (as well as logic in general) is correct thinking. It is the truth which no man of good sense considers as open to argument, and which is expressed as much as possible briefly and precisely. Problems arise at its concretisation whereas just what we nowadays need concerning scientific logic is its subject fixed more particularly in comparison with Chelpanov's time.

Let's look how modern Russian authors of high school textbooks do it.

"The basic (logical) forms in which thoughts are expressed," Yu. Ivlev writes, "are: concept, judgement, theory, etc. The basic forms of development of knowledge are: conclusion, problem, hypothesis, etc.

Logic studies forms of thoughts and of development of knowledge, special ways and methods of knowledge, applied at the stage of abstract thinking, and also special laws of thinking" [2, 8].

Thus the subject of logic is a set of forms of abstract thinking and of development of abstract knowledge. Proceeding to define the subject, Ivlev says that forms of thinking are mainly considered by formal logic whereas forms of development of knowledge by dialectical one, and that "during cognition methods of formal logic are supplemented with methods of dialectical logic and vice versa" [2, 11].

|

|

|

|

Any textbook of logic is, in essence, that of formal logic, instead of general one. |

|

|

It is reasonable to assume, that Ivlev's textbook "Logic" has presented with equal diligence the both variants of logical knowledge specified above. But, having assumed it, we'll make a mistake, and we'll do it not only as regards Ivlev's book. Any textbook of logic is, in essence, that of formal logic, instead of general one, and the formal character of that book should be declared in its very title to not confuse readers, students primarily, not skilled in scientific questions.

Why all textbooks titled "Logic" offer a unilateral, formal material? Because, from the point of view of their authors, there exists no other logic, besides formal one. It is true even in relation to such authors, as Ivlev. It would seem he recognizes dialectical logic as well as formal, but in point of fact it is not so.

Firstly, according to Ivlev, dialectical logic, having its roots in an extreme antiquity, has not nevertheless developed as a science. "For a long time," he says, "the attempts occur to develop dialectical logic, the subject of which consists in special forms and laws of development of knowledge" [2, 11]. It is quite clear that Ivlev does not believe in a positive outcome of these attempts. Another matter is formal logic. Ivlev tells about it very respectfully and even introduces it as "one of the most ancient sciences" [2, 12].

Secondly, dialectical logic in Ivlev's interpretation has not any right to pretend to be considered as a special type of logic which qualitatively differs from formal one. If, as he takes for granted, the subject of dialectical logic consists in forms of development of knowledge this logic is a formal knowledge. It should be a section of formal logic investigating such forms of thinking which are of development. It is curious to point out, that, as we saw earlier, Ivlev attributes conclusion - one of three basic forms of abstract thinking, a doubtless part of the subject of formal logic - to the sphere of interest of dialectics.

|

|

|

Ivlev's textbook

|

The subject of dialectical logic consists not in forms of development, but in development of forms, in content of abstract thinking. To consider thinking as content means to consider moving, changing, developing of its forms. |

|

|

In point of fact the subject of dialectical logic is not at all what Ivlev speaks about, because that consists not in forms of development, but in development of forms, in content of abstract thinking. To consider thinking as content means nothing neither more nor less than to consider moving, changing, developing of its forms.

Not only Ivlev strives to subordinate dialectical logic to formal one. Let's take, for example, V. Kirillov and A. Starchenko: "Learning complex dialectical processes of the objective world, thinking submits at the same time to the laws of formal logic, non-observance of which makes impossible to reflect logic of things" [3, 11].

|

|

|

|

The scornful attitude to dialectical logic leads to representing of general logic unilaterally - only as formal one. |

|

|

The scornful attitude to dialectical logic leads to representing of general logic, which is the whole (both formal and having content) knowledge about correct thinking, defectively, unilaterally - only as formal logic. Meanwhile to learn logic properly it is necessary to take its formal side as well as its dialectical one. Without the equal account of these sides it is impossible to understand logic nowadays and its history.

Look at this history in Ivlev's interpretation [2, 12 - 14]. Firstly, the historical material is given here separately for formal logic and dialectical one, and this approach makes us to think that they are independent from each other. As they both are logic, it is difficult to believe in the lack of a continuous communication between them, but this communication is reflected in their history only in the form of names of Plato and Aristotle.

Secondly, about development of formal logic Ivlev tells much more, than about development of dialectical one, though he notes that the latter is not a knowledge less ancient than the former. At such presentation it is easy to imagine that the history of formal logic, for reasons absolutely unknown, much more rich and interesting than that of dialectics.

Thirdly, all logical development, pictured by Ivlev, looks not development, i.e. internally determined process, but the number of shifts caused only by external reasons. Formal logic was moved forwards, Ivlev suggests, first by needs of oratory, then by inquiries of mathematics. As to dialectical logic, its movement was defined with needs of philosophy - what needs it is not specified.

|

|

|

|

The source of development of logic is struggle of its opposite sides, therefore, when logic is taken unilaterally, its history loses features of development. |

|

|

Why has it turned out so? Why has development, i.e. autonomous movement, of logic disappeared? The source of self-movement of logical knowledge is struggle of its opposite - formal and dialectical - sides, therefore, when logic is taken unilaterally, its history inevitably loses all features of development.

With more or less obvious formal-logical tendency the history of logic is considered in all other high school textbooks. A. Getmanova in her vast sketch [4, 329 - 391] presents it as the history of formal logic diluted by unintelligible additions, devoted to dialectics. For example, about Hegel this sketch enlightens us in such a way: "He criticized Kant, particularly in logic sphere, but his criticism proceeded from positions of idealistic dialectics. Logic from Hegel's point of view coincides with dialectics. Therefore, criticizing formal logic, he rejects it… The rational grain of Hegel's philosophy is dialectics" [4, 342]. It is impossible to understand whether Getmanova abuses or praises Hegel for his dialectics.

There is no dialectics at all in the history of logic given by E. Voishvillo and M. Degtyaryov [5, 33 - 38]. And it is not strange, for these authors know only one logic - formal one. "The subject of logic consists of historically developed forms and ways of knowledge," they categorically declare [5, 21]. At the same time, from their point of view, it is by no means a mistake to consider as that subject correct thinking [5, 9].

|

|

|

Getmanova's textbook

|

If you agree that the subject of logic is correct thinking, you should agree also that this subject consists in form and content of abstract thinking. Thus logic has to work not only with forms of thinking, but also with their contents, i.e. it has to be both formal and dialectical. |

|

|

But, first, there is a sense to discuss correctness of healthy man's thinking (logic studies only such thinking) if his thoughts are abstract, instead of concrete (sensual), and, second, this correctness depends both on form and content of thinking. Therefore, if you (as, in point of fact, everybody) agree that the subject of logic is correct thinking you should agree also that this subject consists in form and content of abstract thinking, or, to say the same somewhat differently, in thinking as abstract form and abstract content. Thus, logic has to work not only with forms of thinking, but also with their contents, i.e. it has to be both formal and dialectical.

The fact that all authors of textbooks titled "Logic" render obvious preference to the formal side of logic, removing dialectics to a background or ignoring it at all as a pseudo-logical knowledge, speaks not so much about their prejudiced attitude or malicious intention, as about their inability to work at philosophical level of logical knowledge. The formal approach to thinking allows to keep one's mind off philosophical problems, the dialectical approach does not allow it at all.

Let's take for instance one of the main principles of, firstly, formal logic and, secondly, dialectical one: the formal principle of identity and the dialectical principle of unity and struggle of opposites.

The principle of identity is usually expressed approximately so: "Any idea is identical to itself." The same may be said easier: "Any idea is only itself." If you want the principle to be written down as briefly as possible, you need use it in the form of mathematical equality: A = A.

|

|

|

Voishvillo's and

Degtyaryov's textbook

|

Each of four main principles of formal logic looks a banal truth, which is doubtful for nobody else but a fool. |

|

|

Are here the depths of philosophy? Not in the least. On the contrary, what we see here is the blunt appeal to ordinary experience, to common sense of the average man. Discussing of the principle of identity seems theoretical tediousness. Each of four main principles of formal logic - not only this one - looks a banal truth, truism, which is doubtful for nobody else but a fool.

Now we shall go to the dialectical principle of unity and struggle of opposites. Usually it is formulated for any subject, including for an idea, taken as a peculiar, non-material subject. We shall recede from the usual formulation of the principle to give it as well as the principle of identity only for an idea, instead of any subject: "Any idea has in itself its opposite and pushes it away from itself."

|

|

|

|

Three main principles of dialectical logic are unevident. Therefore they frighten people inexperienced in philosophy, including authors of textbooks of logic. |

|

|

Here we are immediately overwhelmed by the powerful wave of philosophy. The principle of unity and struggle of opposites defies common sense, sounds as a slap in the face of the average man. If the principle of identity considers any idea as only this idea and nothing else, the principle of unity and struggle prefers to see the subject as initially forking: it is itself and not only itself, itself and its opposite.

Is such a fork of any idea obvious? No, it is not. The contents of two other main principles of dialectical logic, one of which is devoted to passing from quantity to quality and other to negation of negation, are unobvious too. Therefore they also frighten people inexperienced in philosophy, including authors of textbooks of logic. Certainly it is more easier to look at Socrates' well-known words "I know that I know nothing" through a prism of the formal-logical principle of non-contradiction and to see in them only an example of scandalous inconsistency of thinking (so Ivlev has acted [2, 36]), than to search in them for philosophical depths, applying dialectical analysis, which needs a plenty of labour and creativity, but to put directly or indirectly logical illiteracy on Socrates - one of the cleverest representatives of mankind - means to contradict historical facts, not to mention that it looks very ugly.

|

|

|

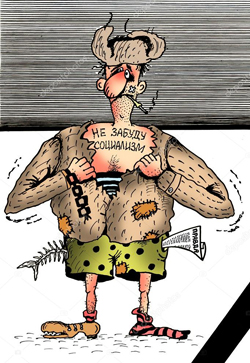

A stupid partisan

of formal logic

|

|

|

|

1. Челпанов Г.И. Учебник логики. - М.: Изд. Группа "Прогресс", 1994. - 248 с.

2. Ивлев Ю.В. Логика: Учебник. - М.: Изд-во МГУ, 1992. - 270 с.

3. Кириллов В.И., Старченко А.А. Логика: Учебник для юридических вузов. - Изд. 5-е, перераб. и доп. - М.: Юристъ, 2002. - 256 с.

4. Гетманова А.Д. Логика: Для педагогических учебных заведений. - М.: Новая школа, 1995. - 416 с.

5. Войшвилло Е.К., Дегтярев М.Г. Логика: Учебник для вузов. - М.: Гуманит. изд. Центр ВЛАДОС, 1998. - 528 с.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

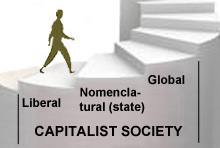

ON THE FORMATIONAL DEVELOPMENT

OF CAPITALIST SOCIETY

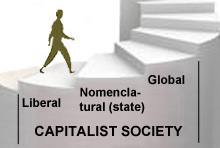

According to the author of the article, it is necessary to divide the capitalist development into three formational stages which correlate to liberal, state and global capitalism.

Key words: K. Marx's theory of formations, the development of Capitalist Society, liberal capitalism, state capitalism, global capitalism.

|

|

|

|

|

|

The facts available to modern scientists testify that the capitalist development has three formational stages |

|

|

It is reasonable, if admitted pre-capitalist society to go through three formational stages, namely, despotic ("Asian"), slaveholding, and feudal, to assume similar triplicity of capitalism. The facts available to modern scientists allow turning it into reliable theoretical knowledge.

However, it is still a prospect which requires overcoming a lot of prejudices. The main one alleges that all principles of capitalist society at any phase of its development are the same.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Had it been the truth, not a prejudice, to try to divide the capitalist development into a number of formational stages would mean to be engaged in such theoretical activity which is as good as worthless. But now it is an obvious prejudice, and I'm sure that K. Marx, the founder of the theory of social formations, if he were alive to this day, would not be fail to carry out formational partitioning of capitalism. Alas, he is not alive. He died many years ago, in 1883, when capitalist society was still on the first stage of its development, and its other stages only just started to appear out of the mist of the future. That is why to make out them was almost impossible.

Under those circumstances the vague outline of the second phase of capitalism was wrongly taken by Marx for approaching communism, classless society. Now it seems naive, but in the 19th century the founders of Marxism as well as all Marxists, both orthodox and revisionist, and even some opponents of Marxism had been convinced that their time was the epoch of transition from class society to classless.

|

|

|

К. Marx |

|

|

In 1848 К. Marx and F. Engels proclaimed capitalism dying. Now we see that they had gone too far |

|

|

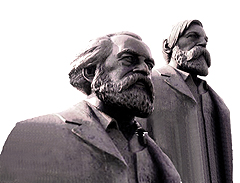

"…The bourgeoisie is unfit any longer to be the ruling class in society, and to impose its conditions of existence upon society as an over-riding law," proclaimed K. Marx and F. Engels in their well-known Manifesto (1848). "It is unfit to rule because it is incompetent to assure an existence to its slave within his slavery, because it cannot help letting him sink into such a state, that it has to feed him, instead of being fed by him. Society can no longer live under this bourgeoisie, in other words, its existence is no longer compatible with society."1 Full of passionate revolutionary impatience, the authors of Manifesto of the Communist Party imagined that development of mankind would be not capitalist but communist any year. More than one century and a half passed since then, but all the world yet lives under the dictation of the bourgeoisie.

In 1918 even F. Mehring, an orthodox Marxist, was compelled to recognize that historical development "was much more slow than the authors of Manifesto had predicted", that, contrary to their opinion, in the middle of the 19th century bourgeois society did not yet reach the last stage of its life. Nevertheless, despite of these facts, Mehring without any hesitations vigorously declared that in the beginning of the 20th century capitalism had got after all to the finish line - to that point where, according to the founders of Marxism, it had been half a century ago. It turns out that Marx and Engels had mistaken only decades2.

F. Mehring is a well-known Marxist-orthodox. Now let's proceed to his ardent ideological opponent, contemporary, and compatriot. I mean E. Bernstein. He is known not less than Mehring, but, unlike the latter, as a Marxist-revisionist. What main features, in Bernstein's opinion, had social life at the dawn of the 20th century? "…The factors of social development which are accessible to scientific research," approved he in 1901, "indicate quite clearly, if you have taken them as a body, the permanent movement which with ever-increasing energy leads modern society towards socialism."3 Thus the German revisionist completely shared Mehring's point of view that capitalism of the beginning of the last century was in agony.

However, characterizing the capitalism as dying, Bernstein, unlike Mehring, considered inexpedient and even harmful any attempts to accelerate the agony of bourgeois society by revolutionary means. In the beginning of the 20th century the proletariat, as the German revisionist fairly believed, still was not ready to take the place of the bourgeoisie as the ruling class. "Despite the great progress which the working class has made on the intellectual, political, and industrial fronts since the time when Marx and Engels were writing," declared he in his most famous work The Preconditions of Socialism and the Tasks of Social Democracy, "I still regard it as being, even today, not yet sufficiently developed to take over political power."4 Then Bernstein hit the nail on the head: "Utopianism is not overcome by transferring or imputing to the present what is to be in the future. We must take the workers as they are. And they are neither universally pauperized, as was predicted in The Communist Manifesto, nor as free from prejudices and weaknesses as their flatterers would have us believe."5

|

|

|

К. Marx and F. Engels  F. Mehring  E. Bernstein |

|

|

|

|

|

"The proletariat, if collated not with an ideal scale but with other classes," ardently objected K. Kautsky, one of the "flatterers" mentioned by Bernstein, the leader of German Social Democracy, "looks, regarding political abilities, more preferable in comparison not only with the petty bourgeoisie and the peasants, but also with the bourgeoisie in general. If we look at parliament, communal self-management or friendly societies where the bourgeoisie and its officials exercise complete sway, we find there stagnation, powerlessness, perversity. As soon as our party gets there, the new life wakes up; our comrades bring initiative, honesty, energy, adherence to principles and make our enemies reanimated by competition."6

Here is another eloquent quote from the same source: "Progressive democracy in modern industrial states is possible only as proletarian democracy. This explains the decline of bourgeois progressive democracy. <…> Only a belief in necessity of the domination of the proletariat and in political maturity of the latter can make now the democratic idea capable to acquire proselytes."7 We see that Kautsky, a Marxist-orthodox, as well as Bernstein, a Marxist-revisionist, connected social progress on the boundary of the 19th and 20th centuries with transition to socialism, and in this respect all political controversy between the famous German Marxists was only tactical: they were arguing about whether Social Democracy should accelerate the agony of capitalism or not.

|

|

|

К. Kautsky |

|

|

Lenin's article Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism represents not so much a scientific analysis of the development of bourgeois formation as a talented propagandist attempt to fix once and for all the social democratic point of view that from the 19th century capitalism is dying |

|

|

In 1916 V.I. Lenin wrote his great article entitled Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism. It represents not so much a scientific analysis of the development of bourgeois formation as a talented propagandist attempt to fix once and for all the social democratic point of view that the early 20th century is undoubtedly the time of dying capitalism. Marxists still account this Lenin's article a fundamental theoretical work, in the Soviet Union it was even placed on a par with Capital8 , though, according to the author's fair evaluation, it is only "a popular sketch".

"Competition becomes transformed into monopoly," states Lenin, drawing on statistics of leading capitalist countries. "The result is immense progress in the socialisation of production. <…> This is something quite different from the old free competition between manufacturers, scattered and out of touch with one another, and producing for an unknown market. Concentration has reached the point at which it is possible to make an approximate estimate of all sources of raw materials … of the whole world. Not only are such estimates made, but these sources are captured by gigantic monopolist associations. <…> Capitalism in its imperialist stage leads directly to the most comprehensive socialisation of production; it, so to speak, drags the capitalists, against their will and consciousness, into some sort of a new social order, a transitional one from complete free competition to complete socialization."9

What is this "new social order"? There is nothing concrete about it in the basic text of Lenin's article, for as explains the foreword which appeared in the structure of the work only in 1917, after the fall of Russian autocracy, "this pamphlet was written with an eye to the tsarist censorship"10. Here we learn also that, in Lenin's opinion, "the period of imperialism is the eve of the socialist revolution"11, and, so, we must mean by "a new social order" such a set-up of society as provides the transition from capitalism to socialism.

This topic is placed in the clearest light in Lenin's The State and revolution. Here the author quotes Critique of the Gotha Programme by Marx, where the latter affirms that "between capitalist and communist society there lies the period of the revolutionary transformation of the one into the over. Corresponding to this is also a political transition period in which the state can be nothing but the revolutionary dictatorship of the proletariat".12 "…Forward development, i.e., development towards communism," echoes Lenin Marx's words, "proceeds through the dictatorship of the proletariat, and cannot do otherwise, for the resistance of the capitalist exploiters cannot be broken by anyone else or in any other way."13

|

|

|

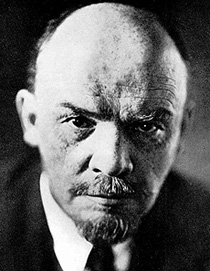

V.I. Lenin |

|

|

Imperialism in Lenin's understanding brings society to the dictatorship of the proletariat |

|

|

So, imperialism in Lenin's understanding is the phase of capitalism which closely, face to face, brings society to the dictatorship of the proletariat. As much as the dictatorship represents, from the Marxist point of view, a temporary, changeful way of governing, which must be rapidly (on the scale of mankind's development) replaced by communist self-government, the founders of Marxism had quite logically come to the conclusion that it is inexpedient to elaborate this theme. Marx "had viewed economic modernization as the historical function of capitalism, neither addressing nor even admitting the possibility of socialists in the role of modernizers," notes S. Cohen. "In addition, he generally declined to speculate about the post-capitalist period in specifics, a tradition his followers found congenial and respected."14 It was communism itself, not transition to communism, that Marx and Engels considered as the theme of their most interest. Nevertheless even communist society they on principle described only in the most general features, extremely abstractly.

Till 1918 the same abstract approach to problems of post-revolutionary social development was held by Lenin, who believed that after the proletariat's victory the question how to exercise authority would be not so much theoretical as practical: in his opinion, the workers, without regard to any prearranged scheme, would understand what should be their dictatorship in this or that concrete situation. At the turn of 1917, when the Bolsheviks seized power, this point of view seemed to prove correct. N.I. Bukharin, one of Bolshevik leaders, wrote in his article Towards socialism, published then, in the first days of the Great October:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

"Plain truth is that with the transition of power to Soviets the bourgeois state falls. The basic, strongest organization of the bourgeoisie - its government - disappears. We build up the new, alternative apparatus of power which is submitted to the proletariat and the peasantry, with the former's obvious overweight as regards organizing forces.

On the other hand, plain truth is also that at factories, in the sphere of economic life, the autocratic regime of the bourgeoisie decays.

The bourgeoisie under the circumstances cannot act there as an organizing force. With growing strength various organs of workers' democracy, first of all factory committees, interfere in business process. But as much as it is the question of nation-wide regulation of industry the transition of power to Soviets makes this regulation practically coinciding with the workers' control.

Under these conditions the basic attributes of the capitalist order of things disappear: the leadership of capital both in politics and in economy falls. There comes the non-capitalist, semi-socialist order of things. The order is still semi-socialist because, first, it is an epoch of dictatorship, not of classless socialism, and, second, has village relations unorganized to a large degree."15

We see that Bukharin impressed by the Bolshevik coup staged with great success obviously indulges in wishful thinking: he presents the desperate attempt of the proletariat of Russia, a backward country16, to overcome the devastation caused by World War I as the transition from capitalism to socialism. What is this - political and economic short-sightedness?

No, Bukharin was not short-sighted. He knew economy of the beginning of the 20th century better than other Bolshevik leaders, including Lenin, and perfectly understood the hardest economic problems the revolutionary proletariat of Russia should solve. "Will the revolution go forward?" considered Bukharin with undisguised worry. "Will it crash itself, having come butt against insuperable difficulties?" Yet he was in an optimistic mood: "It doesn't befit to speak in advance about any insuperable difficulties. They are enormous. Soviet power can more than once stumble over questions of victualling, transport, demobilization of army, over resistance and sabotage of the big bourgeoisie and its supporters. But there is no reason to speak that it will go bust solving these problems. This, people's power is the only one, if any, that can make a number of decisive steps."17

|

|

|

N.I. Bukharin |

|

|

Bukharin and other Marxists of his time had overlooked transition from the primary capitalist formation (liberal capitalism) to the secondary (state capitalism). Instead of this formational transition they saw another one: from capitalism to socialism |

|

|

So, Bukharin was aware of main economic difficulties of Soviet power and had every reason to emphasize that they were enormous. Nevertheless he, as well as all other researchers of economy in his time, did not notice the most essential: in his analysis Bukharin overlooked transition from the primary capitalist formation (liberal capitalism) to the secondary (state capitalism), though the process went on right before his eyes. Instead of this formational transition the Bolsheviks and other Marxists saw another one: from capitalism to socialism. The latter transition also went on in that time, but on another, higher level of abstraction, therefore it had not the first and foremost practical value which Marxist scientists attributed and still attribute to it.

"It is curious to note," wrote Bukharin in Towards socialism, "that our opponents from the camp of moderate socialists and even some bourgeois economists consider state-capitalist regulation quite possible. But the basic difference between the latter and the workers' control is that another class holds power. It is the question of social balance of forces. Transition of power to Soviets means its positive decision."18

|

|

|

|

|

|

As time went on the Russian dictatorship of the proletariat became, from the point of view of classical Marxism, more and more strange. The new society that had been built by the Bolsheviks was state-capitalist, not socialist or communist |

|

|

The matter, in the eye of Bukharin, is easy as pie: it takes only Soviets' victory to make state-capitalist regulation non-capitalist, semi-socialist, proletarian! In practice all appeared much more difficultly. As time went on the Russian dictatorship of the proletariat became, from the point of view of classical Marxism, more and more strange, its proletarian character became more and more phantom. "In the first years after the October Revolution there became quite clear that expected harmony of interests between state and labour had not achieved. On the contrary, the old bureaucratic features had appeared with all acuteness in the new, maladjusted social mechanism. The military-communist policy of strengthening of state centralism had very quickly shown its contradictions with interests not only of the peasantry, but of the working class too."19

And nevertheless a new society had arisen. But it was state-capitalist, not socialist or communist. "In many respects Russian economy and other social forms closely connected with it, having passed through the crucible of fratricidal war and being squeezed in rigid "military-communist" structures, had been doomed to the irreversibility of regeneration in spirit of state pseudo-socialism," writes on this theme V.V. Zhuravlyov20, not understanding that the matter is in the laws of formational movement of capitalist society, not in any features of Russian history. Capitalism inevitably rises from the first, liberal level of its development to the second, state level. In this respect the only specificity of Russia is that here, not anywhere else, was born the first state-capitalist society.

About formational development of capitalism the founders of Marxism knew nothing. Moreover, from their point of view, there are no formational stages in the movement of capital. Marx and Engels considered early, mature and late capitalism only as different periods of existence of the same formation. This point of view was adopted by the Bolsheviks. They, all without exception, regarded capitalism of all periods and of all colours as only capitalism, the form of social life which from the beginning of the 19th century became reactionary, turned to a brake on social progress. If so there is no need to sort out kinds of capitalist society, to find out what of them is better and what is worse. Down with the bourgeoisie - and no more of this! Nevertheless none other than the Bolsheviks who considered that in the 20th century any form of capitalism, including state one, was an anachronism, became the creators of the first state-capitalist society. They did not want, but yet became. How did it happen?

|

|

|

The Bolsheviks put the question rigidly:

capitalism or socialism.

But they had built

state capitalism |

|

|

It turned out that to carry out the proletarian dictatorship in Russia so difficultly that in the spring of 1918 the fierce debate on the principles of building of the new society had arisen in the Bolshevik camp |

|

|

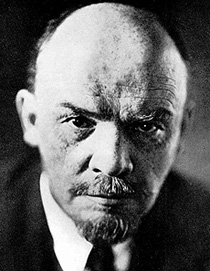

It turned out that to carry out the proletarian dictatorship in Russia, a mediocre capitalist country burdened by numerous feudal vestiges, so difficultly that in the spring of 1918 the fierce debate on the principles of building of the new society had arisen in the Bolshevik camp. Lenin's program article The immediate tasks of the Soviet government acted as a powerful catalyst for this discussion. The author of the article insists that socialism can be constructed only on the basis of the all-round account and control over economic sphere. "The socialist state," convinced Lenin, "can arise only as a network of producers' and consumers' communes, which conscientiously keep account of their production and consumption, economise on labour, and steadily raise the productivity of labour, thus making it possible to reduce the working day to seven, six and even fewer hours. Nothing will be achieved unless the strictest, country-wide, comprehensive accounting and control of grain and the production of grain (and later of all other essential goods), are set going."21

Even if to team up the author of The immediate tasks and to accept for true that in the beginning of 1918 only insignificant minority of the population of the Soviet republic did not sympathize with the Bolsheviks, we must declare the "country-wide accounting and control", for which Lenin called, no more than an unrealizable in that time dream, because the overwhelming majority of inhabitants of Russia, irrespective of approval or disapproval of the Lenin's plan of socialist construction, had not the slightest opportunity to take actively part in realization of this project for the simple reason that were illiterate (73,7%, according the census of 189722). That is why there was only a thin layer of representatives of Soviet power to implement in practice Lenin's accounting and control. Almost universal illiteracy made tremendous opportunities for abuse, and, certainly, they frequently turned to a reality.

|

|

|

V.I. Lenin.

The immediate tasks of the Soviet government |

|

|

Lenin's plan of socialist construction met sharp criticism of "the left communists" |

|

|

Lenin's plan of socialist construction met sharp criticism of "the left communists". It is interesting, that one of their leaders was Bukharin who recently did not see any basic problems in the sphere of proletarian organization of social production.

In April of 1918 the left communists published a series of critical articles, particularly Theses on the current situation. The authors of this document affirmed that in the Soviet republic after the conclusion of the Treaty of Brest Litovsk "there emerged the tendency to deviation of the majority of communist party and Soviet government led by the party" (Lenin and his supporters were implied) "towards petty-bourgeois policy of the new sample"23. "If such tendency has been developed," warned authors of Theses, "the working class will cease to be the head of socialist revolution, the hegemon leading the poorest peasantry to destruct the domination of financial capital and landowners; it will appear the force interspersed in semi-proletarian and petty-bourgeois masses which set themselves the task, instead of proletarian struggle in the union with the West-European proletariat for overthrow of imperialist system, to defense farmers' fatherland against burdens of imperialism, and this task can be solved by a compromise with the latter. If active proletarian policy has abandoned, the gains of workers' and peasants' revolution will start to stiffen in the system of state capitalism and petty-bourgeois economic relations."24

This quote vividly demonstrates what a monstrous theoretical porridge was in heads of "the left communists": in their opinion, thanks to Lenin's plan of socialist construction state capitalism and petty-bourgeois economy can "stiffen" as an integrated economic system, i.e. big capital, instead of ruining petty one, can conclude with it mutually advantageous partner relations! Moreover: Lenin's economic policy, aimed at nationalization, centralization, and integration of capital, for some strange reason was named by "the left communists" "petty-bourgeois"!

|

|

|

|

|

|

Lenin's reply on criticism of "the left communists" is an agitation for state capitalism |

|

|

Lenin's reaction was very sharp, angry. "Evolution in the direction of state capitalism, there you have the evil, the enemy, which we are invited to combat," noted he at the session of the All-Russia Central Executive Committee on April, 29th, 1918. "When I read these references to such enemies in the newspaper of the Left Communists, I ask: what has happened to these people that fragments of book-learning can make them forget reality? Reality tells us that state capitalism would be a step forward. <…> To achieve state capitalism at the present time means putting into effect the accounting and control that the capitalist classes carried out. We see a sample of state capitalism in Germany. We know that Germany has proved superior to us. But if you reflect even slightly on what it would mean if the foundations of such state capitalism were established in Russia, Soviet Russia, everyone who is not out of his senses and has not stuffed his head with fragments of book-learning, would have to say that state capitalism would be our salvation.

I said that state capitalism would be our salvation; if we had it in Russia, the transition to full socialism would be easy, would be within our grasp, because state capitalism is something centralised, calculated, controlled and socialised, and that is exactly what we lack: we are threatened by the element of petty-bourgeois slovenliness, which more than anything else has been developed by the whole history of Russia and her economy, and which prevents us from taking the very step on which the success of socialism depends. <…>

Only the development of state capitalism, only the painstaking establishment of accounting and control, only the strictest organisation and labour discipline, will lead us to socialism. Without this there is no socialism."25

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

"We have introduced workers' control as a law, but this law is only just beginning to operate and is only just beginning to penetrate the minds of broad sections of the proletariat," ascertains discontentedly the author of The immediate tasks of the Soviet government. "In our agitation we do not sufficiently explain that lack of accounting and control in the production and distribution of goods means the death of the rudiments of socialism, means the embezzlement of state funds (for all property belongs to the state and the state is the Soviet state in which power belongs to the majority of the working people). We do not sufficiently explain that carelessness in accounting and control is downright aiding and abetting the German and the Russian Kornilovs, who can overthrow the power of the working people only if we fail to cope with the task of accounting and control, and who, with the aid of the whole of the rural bourgeoisie, with the aid of the Constitutional-Democrats, the Mensheviks and the Right Socialist-Revolutionaries, are "watching" us and waiting for an opportune moment to attack us. And the advanced workers and peasants do not think and speak about this sufficiently. Until workers' control has become a fact, until the advanced workers have organised and carried out a victorious and ruthless crusade against the violators of this control, or against those who are careless in matters of control, it will be impossible to pass from the first step (from workers' control) to the second step towards socialism, i.e., to pass on to workers' regulation of production."26

What is this about? Workers' control exists only on a paper, formally, for even the advanced workers do not understand its importance as the first step to socialist management. We see Lenin angry, he criticizes himself, other Bolsheviks, the people of Russia as a whole for insufficient consciousness and activity in constructing of socialism, but if even he, the ideological inspirer and the leader of the Great October, was insufficiently conscious and active what did he wait from other builders of socialist society and what right did he have to demand from these people, the overwhelming majority from which was elementary illiterate, the country-wide accounting and control?

The leader of the October had the greatest ideal - Communist Society. It permanently conducted him. It conducted and attracted, like Bluebird. However when the Bolsheviks had been urged by Russian reality to use state-capitalist methods for socialist building, their leader quickly realized the requirement alien to his ideal and immediately, although with reluctance, made all appropriate changes in the Soviet economic policy. It was one of Lenin's main advantages he had as the head of the country: to see real life as striving for an ideal.

|

|

|

|

|

|

In the development of state-capitalist sector of economy Lenin wrongly saw becoming socialism |

|

|

It is necessary to emphasize, however, that, from the point of view of adequate reflection of reality, Lenin's attitude to state capitalism was rather far from serving as the sample to follow: in the development of state-capitalist sector of economy the leader of the Bolsheviks wrongly saw becoming socialism, instead of a new capitalist formation, more powerful and aggressive, more hostile to communist ideas than old, liberal capitalism. It ensued his essential underestimation of the danger of nationalization of market economy for the working class going to communism. As a result of this formational mistake Lenin vigorously propagandized state capitalism deeply hostile to socialism as the basis of the latter, acting as a conductor of state-capitalist ideas in working environment, not as the leader of the proletariat. So he, without knowing and wishing, paved the way for state capitalism.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bukharin better, than Lenin, felt the danger of state capitalism to proletarian power |

|

|

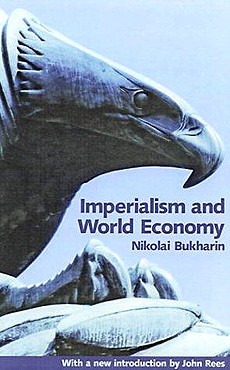

Bukharin more carefully, than Lenin, studied tendencies of the world economy (it is clearly visible at comparison of two works on this theme: Bukharin's Imperialism and World economy and Lenin's Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism) and, consequently, he better, than Lenin, felt the danger of state capitalism to proletarian power. Bukharin's economic views were generated under the influence of the German social-democrat R. Hilferding who approved in his book Finance capital that in the beginning of the 20th century capitalist society did not degrade. On the contrary, it had progressed to the new level the main feature of which was domination of unified ("finance" as it was expressed by Hilferding) capital: "Industrial, trading and banking capital, earlier separate spheres, are put now under the management of financial aristocracy which unites masters of industry and banks in close personal union."27 Thus, the author of Finance capital emphasizes that spontaneous capitalism becomes organized.

Bukharin had gone further, having developed the concept of organized capitalism up to the concept of state capitalism. Nowadays, as he writes in Imperialism and World economy, in the vast of the world market unprecedented "gigantic, consolidated, and organized economic bodies possessed of a colossal fighting capacity" are locked in the fierce struggle28. Under these circumstances the government of the bourgeois state becomes the supreme body of "the state capitalist trust", the integrated political-economic organization of all national enterprises29. What a striking contrast to that decrepit, rotting monopoly capitalism which we see in Lenin's Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism! According to Bukharin's point of view, consolidation of national economic structures in state capitalist trusts means strengthening of capitalism, not rotting. It draws the disturbing conclusion which we see in the Russian version of Imperialism and World economy but which is absent for some reason in the English one: the modern proletariat "meets on its way the constantly growing force of close ranks of the bourgeoisie".30

|

|

|

N.I. Bukharin.

Imperialism and World economy.

A modern publication

in English |

|

|

|

|

|

"Although Bukharin exaggerated the extent and permanency of "statization" and trustification in 1915 - 1916, he pinpointed a basic twentieth-century development," S. Cohen marks. "The following decades did witness the final disappearance of laissez-faire capitalism and the emergence of a new kind of economically active state, ranging in type and degree of intervention from administered capitalism and the welfare state to the highly mobilized economies of Soviet Russia and wartime Nazi Germany."31

However even Bukharin, who had better than others realized the nature of state capitalism, could not rise up to clear understanding of it as the secondary capitalist formation opposite to the initial, liberal one. The contrast of these formations had and has such powerful disorientating influence on all researchers of modern economy, both Marxists and non-Marxists, that they quite often confuse state capitalism, on the one hand, with socialism, and, on the other hand, with oligarchic capitalism, i.e. with the last phase of liberal capitalism on which few of monopolists (bourgeois oligarchy) control all social institutes including the state.

Here, for example, the quote from Bukharin's Imperialism and World economy where the author describes the birth of a state capitalist society: "… Various spheres of the concentration and organization process stimulate each other, creating a very strong tendency towards transforming the entire national economy into one gigantic combined enterprise under the tutelage of the financial kings and the capitalist state, an enterprise which monopolises the national market and forms the prerequisite for organized production on a higher non-capitalist level."32 In the beginning of the quote the author gives us a fine, exact image of a state capitalist society (a country-trust), but further Bukharin declares that this society is "under the tutelage of the financial kings" and at once makes the image he gives us defective: instead of the harmonious steel pyramid of workers of a country-trust where all men, from the bottom to the top, are fighters of the same political-economic army, where there are no class partitions and, consequently, each soldier can become a general, instead of all this awful magnificence we see now an angular and friable hierarchy of feudal type with the bunch of fatting oligarchs, kings of business, haughtily sitting on the top like on the throne. It is easy enough to knock them off the top: they tease the working people with their indecent richness and thus provoke civil commotion. But they are not leaders of a country-trust, they are just market monopolists who have control over state for maximizing their profits.

|

|

|

S. Cohen |

|

|

Bukharin and Lenin cosidered bourgeois oligarchic society as the direct prerequisite for socialist one though actually on the basis of oligarchic capitalism there arises state capitalism, not socialism |

|

|

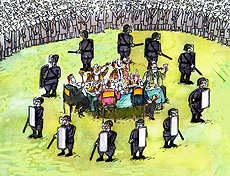

Bukharin, as well as Lenin, presents bourgeois oligarchic society as the direct prerequisite for socialist one though actually on the basis of oligarchic capitalism there arises state capitalism, not socialism. Moreover: even state capitalism, the second stage of the development of bourgeois society, is not yet the direct prerequisite for socialism, because the development has three formational stages. The third stage is global capitalism. On this level the world economy will function as one and only world trust.

Bukharin and Lenin considered global capitalism as only a theoretical invention, a speculative hypothesis lacking solid connection with the real development of capitalist society. Here is what Bukharin replied to the question "Can it happen so that there will be a world trust?": "This possibility would be thinkable if we were to look at the social process as a purely mechanical one, without counting the forces that are hostile to the policy of imperialism. In reality, however, the wars that will follow each other on an ever larger scale must inevitably result in a shifting of the social forces. The centralisation process, looked at from the capitalist angle, will inevitably clash with a socio-political tendency that is antagonistic to the former. Therefore it can by no means reach its logical end; it suffers collapse and achieves completion only in a new, purefied, non-capitalist form."33

Lenin's answer to the same question was similar: "There is no doubt that the development is going in the direction of a single world trust that will swallow up all enterprises and all states without exception. But the development in this direction is proceeding under such stress, with such a tempo, with such contradictions, conflicts, and convulsions - not only economical, but also political, national, etc., etc. - that before a single world trust will be reached, before the respective national finance capitals will have formed a world union of "ultra-imperialism", imperialism will inevitably explode, capitalism will turn into its opposite."34

|

|

|

Oligarchic democracy |

|

|

Bukharin's and Lenin's denying of real possibility of global capitalism proceeds from the assumption that such social system would be useful only to the bourgeoisie, that the proletariat absolutely need not it |

|

|

Bukharin's and Lenin's reasons against global capitalism are unpersuasive. They both proceed from the assumption that such social system would be useful only to the bourgeoisie, that the proletariat absolutely need not it. This assumption is evidently false: a world trust will eliminate world economic crises which hit the proletariat not less than the bourgeoisie, hence, global capitalism is useful to all classes. And it is not casual that nowadays, when social problems are beginning to be perceptibly global, more and more people come to the conclusion that these problems can be overcome only by globally organized mankind.

For social problems dangerously grow, the theme of globalization of social life, already extremely actual, will be, no doubt, the most important point in the nearest future. Whatever the anti-globalists do, the number and the strength of the globalists will grow, because the further development of society is impossible without the movement towards global capitalism.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

"Globalization," writes the Swedish historian J. Norberg, "has been often perceived as a threat, as something that can be good for "others" and to what "we" are compelled to adapt. Earlier I myself considered so, however I have changed my opinion owing to convincing facts: their abundance testifies that globalization is a unique chance for all world."35

About what facts there is a speech? Globalization, emphasizes Norberg, promotes development of capitalist economy as releases a society from a despotic arbitrariness both private businessmen, and state-capitalist bureaucracy: "Our options and opportunities have multiplied as transportation costs have fallen, as we have acquired new and more efficient means of communication, and as trade and capital movements have been liberalized.

We don't have to shop with the big local company; we can turn to a foreign competitor. We don't have to work for the village's one and only employer; we can seek out alternative opportunities. We don't have to make do with local cultural amenities; the world's culture is at our disposal. We don't have to spend our whole lives in one place; we can travel and relocate."36

|

|

|

J. Norberg |

|

|

In the coming neoliberal world the Swedish historian J. Norberg sees only positive signs. It entails his impetuous puffery of the new, third capitalist formation |

|

|

In the coming neoliberal world the Swedish historian sees only positive signs. It entails his impetuous puffery of the new, third capitalist formation. Norberg, a sweet singing troubadour of globalization, does not see that it implies unprecedented strengthening of the exploitation of labour, that every free worker of the global world, trying to remain free, will be compelled to act as a universal working force, i.e. such a working force which is capable to make itself adjusted for any work necessary for the global market. But the positive signs of globalization, which have been noticed by Norberg, really exist, therefore someday global capitalism will come, if, certainly, before this moment the mankind has not ruined itself in world wars.

1. Маркс К., Энгельс Ф. Сочинения. Изд. 2-е. Т. 4. М., 1955. С. 435.

2. Меринг Ф. Карл Маркс. История его жизни. М., 1990. С. 146.

3. Бернштейн Э. Возможен ли научный социализм? // Э. Бернштейн. Возможен ли научный социализм? Ответ Г. Плеханова. Одесса, 1906. С. 35.

4. "Trotz der grossen Fortschritte, welche die Arbeiterklasse in intellektueller, politischer und gewerblicher Einsicht seit den Tagen gemacht hat, wo Marx und Engels schrieben, halte ich sie doch selbst heute noch nicht f?r entwickelt genug, die politische Herrschaft zu ubernehmen" (Bernstein Ed. Die Voraussetzungen des Sozialismus und die Aufhaben der Sozialdemokratie. Stuttgart, 1899. S. 183 - 184.).

5. "Man hat den Utopismus noch nicht uberwunden, wenn man das, was in der Zukunft werden soll, spekulativ in die Gegenwart verlegt, bezw. der Gegenwart andichtet. Wir haben die Arbeiter so zu nehmen wie sie sind. Und sie sind weder so allgemein verpaupert, wie es im Kommunistischen Manifest vorausgesehen ward, noch so frei von Vorurtheilen und Schwachen, wie es ihre Hoflinge uns glauben machen wollen" (Ibid. S. 184.).

6. Каутский К. К критике теории и практики марксизма. М., 2003. С. 294.

7. Там же.

8. "Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism directly continues and develops Capital by K. Marx" (ФЭС. М., 1989. С. 210.).

9. Ленин В.И. Полное собрание сочинений. Т. 27. М., 1980. С. 320 - 321.

10. Там же. С. 301.

11. Там же.

12. Маркс К., Энгельс Ф. Сочинения. Изд. 2-е. Т. 19. М., 1961. С. 27.

13. Ленин В.И. Полное собрание сочинений. Т. 33. М., 1981. С. 88.

14. Коэн С. Бухарин. Политическая биография. 1888 - 1938. М., 1988. С. 83.

15. Бухарин Н.И. К социализму // Возвращённая публицистика. Кн. 1. М., 1991. С. 111.

16. In the beginning of the 20th century the overwhelming majority of the population of Russia - 87% - was rural (История СССР, 1861 - 1917. М., 1984. С. 191.).

17. Бухарин Н.И. К социализму // Возвращённая публицистика. Кн. 1. М., 1991. С. 113.

18. Там же. С. 112 - 113.

19. Наше Отечество (Опыт политической истории). Часть II. М., 1991. С. 77.

20. Политические партии России: история и современность. М., 2000. С. 404.

21. Ленин В.И. Полное собрание сочинений. Т. 36. С. 185.

22. Наше Отечество (Опыт политической истории). Часть I. М., 1991. С. 204.

23. Тезисы левых коммунистов о текущем моменте // Левые коммунисты в России. 1918 - 1930 гг. М., 2008. С. 157.

24. Там же. С. 157 - 158.

25. Ленин В.И. Полное собрание сочинений. Т. 36. М., 1981. С. 254 - 258.

26. Ленин В.И. Полное собрание сочинений. Т. 36. М., 1981. С. 185.

27. Гильфердинг Р. Финансовый капитал. М., 1924. С. 351.

28. Бухарин Н.И. Проблемы теории и практики социализма. М., 1989. С. 80.

29. Там же. С. 83.

30. Бухарин Н.И. Проблемы теории и практики социализма. М., 1989. С. 83.

31. Коэн С. Бухарин. Политическая биография. 1888 - 1938. М., 1988. С. 60.

32. Бухарин Н.И. Проблемы теории и практики социализма. М., 1989. С. 53.

33. Там же. С. 93.

34. Ленин В.И. Полное собрание сочинений. Т. 27. М., 1980. С. 98.

35. Норберг Ю. В защиту глобального капитализма. М., 2007. С. 7.

36. Там же. С. 12.

|

|

|

A sample of advertising

for global capitalism:

the world of wonderful prospects |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

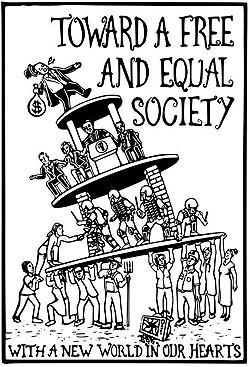

THE DIFFICULT WAY TO SOCIALISM

Reflections on the margins of the book "Towards a New Socialism" by W.P. Cockshott and A. Cottrell

Introduction

|

|

|

|

|

W.P. Cockshott and A. Cottrell (C&C) are, above all, two responsive persons who deeply experience the injustice of capitalism and seek ways to eliminate it |

|

|

The book "Towards a New Socialism" by W.P. Cockshott and A. Cottrell (for brevity we will use the abbreviations "TNS" and "C&C") is of considerable interest not only to Marxist scholars and other sociologists. TNS's authors are not bookworms, learned bores, for whom the creation of conceptual constructions is a prestigious gymnastics for the mind, allowing them to be considered intellectuals of the highest standard and thereby earn a comfortable life. No, C&C are, above all, two responsive persons who deeply experience the injustice of capitalism and seek ways to eliminate it. That is why it is very useful to get acquainted with their book for everyone for whom a just society is not just a beautiful dream, but an ideal, the practical implementation of which will save humanity from early death.

This does not mean that it's easy to read TNS. The authors sometimes lack literary skill, clarity of views, system presentation, but the main difficulty in reading their work is that the topic raised by C&C is one of the most complex in modern science. TNS is focused on a comprehensive solution to the most important social issues of modern civilization. They are diverse, complex, intricately intertwined, and, in addition, constantly growing quantitatively and qualitatively, so unraveling this growing tangle of contradictions is far from easy. And if it has led to some results, describing them is also not easy. Undoubtedly, when C&C took up such an unraveling, they saw clearly that their work would be hard, but it didn't stop them, and they did manage to develop a good version of a comprehensive solution to modern problems. Honor and glory to them for that. Let us discuss the work by C&C, and if it turns out that they were mistaken somewhere, we will not judge them too harshly.

On the crisis of the left movement

C&C began their reflections on socialism with a statement of the deep crisis of the left movement. The collapse of the "socialist camp" led by the USSR reinforced the disagreements of left theorists on what a socialist society should be like. The extreme positions were taken, on the one hand, by the social democrats and, on the other hand, by those whom C&C christened "idealist Marxists" (as will be shown below, it is better to call them orthodox Marxists): the former claim that Soviet socialism collapsed because it was not democratic, and the latter - because it was not socialism. "The social democrats may accept that the Soviet system was indeed Marxist, and they reject Marxism; idealist Marxists cling to their theory while claiming that it has not yet been put into practice."1

Both of these extreme points of view, according to C&C, are flawed. The position of social democracy does not suit TNS's authors with its philistine groundedness and sweeping denial of the existence of any positive qualities in Soviet socialism. Social democracy, C&C say, offers "insufficiently radical solution to the ills of modern capitalist societies,"2 and indeed, for a typical social democrat, socialism is just a process of gradually improving the working conditions of the workers through reforms that in no way encroach on the foundations of capitalism. As for "idealist Marxists", C&C do not like them for their separation from reality, and more specifically, for their denial of the socialist nature of any Soviet-type society because of its inconsistency with the socialism of the classics of Marxism. TNS's authors believe that although this discrepancy does exist, it is not a sufficient reason to deny a socialist character of such societies, for, according to C&C, no concrete historical society is "the incarnation of an Idea".3

|

|

|

"Towards a New Socialism"

by Cockshott and Cottrell

W.P. Cockshott

A. Cottrell

|

|

In our opinion, the criticism by TNS's authors of both the position of social democrats and the position of orthodox Marxists ("idealist Marxists") cannot be considered impeccable. |

|

|

In our opinion, the criticism by TNS's authors of both the position of social democrats and the position of orthodox Marxists ("idealist Marxists") cannot be considered impeccable.

Social democracy, of course, is wrong in calling its capitalist charity socialist and all sorts of attempts to act more radically pseudo-socialist, since from the time of More and Campanella it is customary to associate socialism with not smoothing out capitalist contradictions, but resolutely eliminating them. In fact, social democrats replace the theme of socialism as a just society, which is qualitatively different from a capitalist one, with the theme of capitalist reforms. However, the neglect of social democracy to the experience of the countries of "real socialism" is not without common sense: in terms of improving the lives of workers and the development of democracy, Soviet socialism has not been very successful, which cannot but cause serious doubts about its socialist character.

Another extreme position is also presented by C&C in a simplified form. The orthodox Marxist, in fact, sin by lack of desire and ability to take into account the real conditions for building socialism, but, when they demand to evaluate any socialist activity from the point of view of the theory of socialism developed by the classics of Marxism, they are absolutely right if some false aspects are not found in this theory. And one should not get away from the demand with a statement that there is no concrete historical society that would be "the incarnation of an Idea". Well, there is not, if the incarnation of some ideal image means a supernatural embodiment, i.e. a materialization that allows the image to remain ideal after taking a material form. However, Marxists usually do not mean such an embodiment when they require socialists to be guided by the ideals of the classics of Marxism: they demand the realization, not the divine embodiment, of these ideals. And if the ideals are not deified, there is no idealism here. An idealist Marxist and a normal Marxist differ from each other not in that the former has ideals, but the latter does not. The difference between them is different: the former deifies his ideals and seeks to translate them into reality even when they are clearly unrealizable; the second, when he sees the unrealizability of his ideals in practice, corrects them so that their realization becomes possible.

|

|

|

A social democrat |

|

The position of C&C: Soviet socialism was socialism, but imperfect and insufficiently Marxist, while a more developed and at the same time Marxist form of socialism is possible |

|

|

So, the defectiveness of the extreme positions occupied by left theorists is not clearly shown in TNS, and as a result, the position formed by C&C is also not clear. Here is its essence: Soviet socialism was socialism, but imperfect and insufficiently Marxist, while a more developed and at the same time Marxist form of socialism is possible.4 There is obviously a desire here to bring all socialists - both those who consider the Soviet system reactionary and those who defend it - to a compromise in order to overcome the crisis of the left movement. However, as history teaches, no crisis can be overcome through compromise.

Liberal and nomenclatural capitalism

"Soviet society was indeed socialist," C&C assert, but immediately add that it "had many undesirable and problematic features."5 It turns out that true socialism, i.e. socialism of the classics of Marxism, is so imperfect that it allows massive repression, exploitation of the working people and infringement of their civil rights? According to C&C, this is so. It means that they unwittingly play along with those who ascribe the vices which are a characteristic of capitalism to socialism. "The Stalin cult, with both its populist and terrible aspects, was central to the Soviet mode of extraction of a surplus product."6 It turns out that the socialist mode of production can naturally have "terrible aspects"! Good socialism!

|

|

|

The enemies of socialism like to picture it

as ancient despotism or as Gulag:   |

|

In fact, Soviet society is antagonistic, and it is not the proletariat that dominates it, but the nomenclature. The exploitation is carried out by the nomenclature indirectly, through the state, but this form of exploitation does not abolish its capitalist character |

|

|

In fact, Soviet society is antagonistic, and it is not the proletariat that dominates it, but the nomenclature - a class that exploits working people on behalf of "people's" state. This is perfectly shown in the book "The nomenclature" by M.S. Voslensky.7 True, Voslensky claims that the Soviet system is not capitalist, and the nomenclature is not the bourgeoisie, but the facts tell a different story: the nomenclature exploits the workers through appropriating the surplus value the latter produce, which means capitalist exploitation.

It is confusing to many that this exploitation is carried out by the nomenclature indirectly, through the state, but this form of exploitation does not abolish its capitalist character: although nomenclatural (state) capitalism is the opposite of classical (liberal) one, it is capitalism. And it arises as a natural result of the monopolization of liberal capitalism. The nationalization of the capitalist economy became widespread already in the 19th century, and in order to avoid misunderstandings, Engels specifically noted that the transfer of private enterprises and even the entire national economy into the ownership of the capitalist state is not yet socialism. "The modern state, whatever its form," he says in Anti-Duhring, "is an essencially capitalist machine; it is the state of the capitalists, the ideal collective body of all capitalists. The more productive forces it takes over as its property, the more it becomes the real collective body of all the capitalists, the more citizens it exploits."8

|

|

|

M.S. Voslensky  |

|

The main feature of nomenclatural property is that it is collective. At the same time, the property consists of shares that cannot be bought or sold by someone from its co-owners. |

|

|

The main feature of nomenclatural property is that it is collective. At the same time, the property, unlike corporate liberal, consists of shares that cannot be bought or sold by someone from its co-owners. You get a share of the property "if you become a member of the nomenclature. The share increases or decreases depending on your position in the hierarchical structure, and you lose your share if you are expelled from the nomenclature. In no case may a member of the class get his share of the capital in his hands. But he regularly receives a certain amount of material benefits, which can be quite accurately calculated and may be compared with the payment of dividends..."9

The struggle between liberal and nomenclatural forms of capitalism will inevitably lead it to the stage of global capitalism, in which the whole world will turn into a single capitalist enterprise. I wrote about this in more detail in my article "On the formational development of capitalist society"10 and in a short philosophy course published on my website.11

|

|

|

"Nomenclature"

by M.S. Voslensky |

|

It must be recognized that socialism will not replace capitalism before the latter passes its three steps corresponding to liberal, nomenclatural (state) and global capitalism. The first step is already behind, the second is almost over, the third is yet to come. |

|

|

Thus, in order to overcome the crisis of the left movement, it is necessary to develop a more scientific idea of the development of mankind, or, speaking the Marxist language, it is necessary to modernize Marx's theory of formations on the basis of the knowledge accumulated over the past decades. And first of all, it must be recognized that socialism will not replace capitalism before the latter passes its three steps corresponding to liberal, nomenclatural (state) and global capitalism. The first step is already behind, the second is almost over, the third is yet to come. In addition, it is necessary to clarify the concept of socialism in order to give a fitting rebuff to those villains who, using the vague ideas of the socialists, have adapted themselves to stain socialist society with capitalist filth. In Marxism, socialism is understood either as the first phase of communism or the last class society, i.e. the society of the dictatorship of the proletariat (the second understanding, in our opinion, is better). Only these meanings of the term "socialism" are acceptable for a Marxist, but both of them are not suitable for characterizing what is called "real socialism", because, from the Marxist point of view, the latter is not socialism, but capitalism.

From Soviet to Post-Soviet socialism

|

|

|

A sample of advertising

for global capitalism:

the world of wonderful prospects |

|

|

|

|

Which version of "real socialism" is better - social democratic or Soviet? Making their choice, C&C did as the Marxists should do: they analyzed the basic economic relations that prevail in both cases. Socialism of the social democrats is clearly fake. In its characteristic "mixed economy", C&C emphasize, "the socialist elements have remained subordinated to the capitalist elements," because "the commodity and wages forms have remained the primary forms of organization of production and payment of labour respectively." As a result, any social democratic government is completely dependent on the capitalist mechanism for wealth-creation.12

On the contrary, the economy of Soviet socialism, according to C&C, has a non-capitalist character: "Soviet socialism, particularly following the introduction of the first five-year plan under Stalin in the late 1920s, introduced a new and non-capitalist mode of extraction of a surplus."13 Why did the experienced Marxist economists Cockshott and Cottrell accept the capitalist relations of the Soviet mode of production as non-capitalist? They were confused by the sharp difference between the Soviet economy and the classical, liberal economy which is described in detail in "Capital".

|

|

|

Social democratic socialism is

a capitalist mirage |

|

C&C admit that Soviet society was socialist, but all important political decisions in the USSR were made by the nomenclature. It is this bourgeois class that must bear responsibility for all the crimes committed by the Soviet government. |

|

|

Yes, C&C admit, the Soviet economy is commodity-money, but, they emphasize, both commodities and money are circulating here in a significantly different way than under classical capitalism. "Under Soviet planning, the division between the necessary and surplus portions of the social product was the result of political decisions."14 TNS's authors did not specify whose decisions these were, but in vain, for by posing this question and finding a scientific answer to it, they would have avoided the erroneous assertion that Soviet society was socialist in nature. If political decisions in the USSR were made by the Soviet proletariat or with its direct participation, as C&C seem to believe, then, in particular, it turns out that this progressive, from the Marxist point of view, class is directly guilty of the mass hunger organized by the Soviet government in 1932 - 1933. This monstrous crime swept over the vast territories of the USSR and killed hundreds of thousands of people. In fact, in any Soviet-type society, all important political decisions are made not by the proletariat, but by the nomenclature - the class of owners of shares of state capital. It is this bourgeois class that must bear responsibility for all the crimes committed by the Soviet government.

The Soviet planned distribution of resources between heavy industry and production of consumer goods within the framework of a pre-made social decision, C&C note, in general terms corresponds to the planning of social production that Marx dreamed of. "Only Marx," TNS's authors make a reservation, "had imagined this 'social decision' as being radically democratic, so that the production of the surplus would have an intrinsic legitimacy."15 This reservation is of fundamental importance: without it, one would think that Marx considered any planned economy - both democratic and undemocratic - as socialist. In fact, this is not so, and Marx, of course, did not dream of planning an economy in which resources are distributed not in the interests of the working class, but in the interests of those who exploit it.

|

|

|

A victim of Soviet "socialism" |

|

In the course of their work, C&C came to the following idea: "The principal bases for a post-Soviet socialism must be radical democracy and efficient planning." In fact, the entire content of TNS is a concretization of this fundamental conclusion. |

|

|